China Progresses Toward Long March 5 Return to Flight via YF-77 Engine Testing

China has resumed testing of a modified version of the country’s most-powerful, full-cryogenic rocket engine as part of the return to flight effort for the Long March 5 heavy-lift rocket that encountered a failure last year due to a problem with one of two YF-77 engines installed on its core stage. Critical missions like a high-profile lunar sample return had to be pushed as a result of the failure and China is gearing up to return the Long March 5 to the launch pad in the second half of this year for another test flight, implementing design changes on the cryogenic main engines of the vehicle.

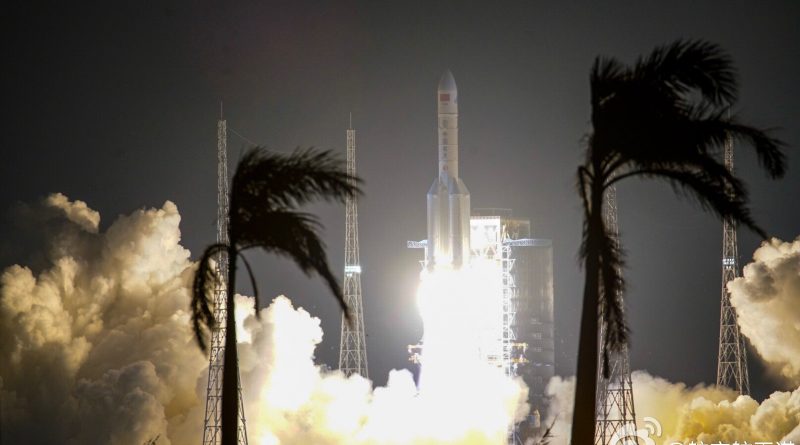

Long March 5 Y2 blasted off from the Wenchang Satellite Launch Center on July 2, 2017 on its second shakedown mission following a successful debut in November 2016. The flight appeared normal while the rocket fired its four Kerosene-fueled boosters and cryogenic core stage in unison to push out of the dense atmosphere and toward orbit with the Shijian-18 experimental satellite that was to debut a new spacecraft platform and various innovative technologies.

Trouble struck around five minutes and 47 seconds into the flight when a gaseous plume began emanating from the rocket’s base where the two YF-77 engines were firing to lift it into space.

Performance data at mission control showed a significant underperformance of the first stage and the rocket’s second stage started its engines just shy of ten minutes into the flight in an attempt to compensate but continued to lose altitude and eventually re-entered the atmosphere over the Philippine Sea.

The test flight failure was a very public one as live video from the falling rocket was available through the operation of the wounded first stage and Chinese space officials acknowledged the failure within a few hours. However, as has become the usual Modus operandi, no details on the ensuing investigation into the root cause of the failure were provided through official channels.

By late September 2017, the future schedule for Long March 5 missions had been adjusted – pushing the planned Chang’e 5 lunar sample return from November 2017 into the second half of 2018 or 2019 while the launch of the Tianhe Core Module of the Chinese Space Station also slipped from 2018 into 2019 to provide sufficient time for corrective measures to be implemented, tested and flown on another test mission. The China Great Wall Industry Corporation confirmed by early October that the cause of the failure was related to the propulsion on the first stage, though work to pin-point the root cause was still ongoing.

Also in October, ship-tracking websites showed China’s Xiang Yang Hong 09 research vessel, carrying the JiaoLong submarine, was in the area of the Philippine Sea where the debris of the CZ-5 first stage splashed down. Sources later confirmed that the vessel was to perform a survey to assess whether a salvage operation could be attempted to recover the remains of the first stage for forensic analysis on the engine section.

Unconfirmed reports emerged in late November, citing sources within the Long March 5 Program Directorate, that the cause of the failure was pin-pointed. According to this unconfirmed information, the cause of the failure was a structural problem causing the turbopump rotor shaft enclosure cap within one of the YF-77 engines to break off and create a blockage within the propellant line.

Official comments made by Tianjin Long March Launch Vehicle Manufacturing Co. – producer of the CZ-5 and 7 rockets, confirmed that the cause of the failure was identified by late 2017 and design changes on the YF-77 engines were being implemented. Testing of the upgraded engine design began in mid-February at the Academy of Aerospace Propulsion Technology (AAPT) test facility near Xi’an. This marked the first of several YF-77 test firings planned in the first half of the year to a) verify the correct cause was identified for the CZ-5 Y2 failure and b) fully qualify changes made to the turbopump design in preparation for the next launch of the Long March 5.

It is understood that the Long March 5 Y3 mission will employ a set of newly built YF-77 engines implementing the changes identified in the wake of the failure. An existing batch of YF-77 units is to undergo inspections and modification followed by acceptance testing before being available for future flights.

YF-77 is China’s most-powerful full-cryogenic engine and the country’s first designed for booster application, generating a launch thrust of 510 Kilonewtons. The engine entered development back in 2002 with initial prototype test firings in 2004 ahead of a lengthy road toward full qualification testing in 2013 across 12 engine units. YF-77 employs the more simplistic open cycle gas generator design with a central gas generator delivering high-pressure combustion gas to drive separate turbopumps on the oxidizer and fuel sides, each with its own gas generator exhaust.

The goal for YF-77 was developing a low-cost engine suitable for use on an expendable rocket, opting for a moderate-thrust engine to be used in a dual configuration instead of developing a more complex engine that could be flown in a single-engine configuration.

Many of China’s future space prospects hinge on the success of the Long March 5 rocket, currently the third most-powerful rocket in operation after SpaceX’s recently-debuted Falcon Heavy and ULA’s Delta IV Heavy. Comprising four Kerosene-LOX boosters powered by China’s YF-100 engine and two five-meter diameter cryogenic rocket stages, Long March 5 can lift up to 23 metric tons into Low Earth Orbit in its current configuration and up to 13 t into a Geostationary Transfer Orbit, around 50% of Falcon Heavy’s expendable capacity.

Long March 5 has been built to further China’s ambitions in the field of robotic exploration of the solar system and it will also be called upon for the heavy-lift business of launching sizeable Space Station modules. However, China is only willing to commit to launching these high-profile payloads after successful testing of the launch vehicle, placing some pressure on the planned test mission.

The Long March 5 Y3 mission will carry Shijian-20, a replacement for the lost Shijian-18. Like SJ-18, the satellite is based on the new ultra-high-performance DFH-5 satellite platform featuring innovative systems like high-thrust ion propulsion, laser communications and ultra-secure quantum communications. Based on the DFH-5 satellite platform, Shijian-18 was the heaviest non-classified Geostationary Satellite ever launched, weighing in at just over seven metric tons according to press reports.

The DFH-5 platform builds on China’s current-generation DFH-4 but triples its payload capacity, hosting communications packages up to 2,200 Kilograms with a payload power up to a whopping 28 Kilowatts, surpassing the most powerful commercial platforms currently on the market. DFH-5 inaugurates innovative systems like a truss acting as structural backbone, twice-deploying solar arrays, high-thrust ion engines for orbit control and a new type of self-controlling propellant system.