Astronauts Repair ISS Power System – Spacewalk ends early after Space Suit Water Intrusion

Astronauts Tim Kopra and Tim Peake ventured outside the hatches of the International Space Station on Friday to embark on a spacewalk dedicated to the restoration of the Station’s Electrical Power System by replacing a failed voltage regulator. A successful replacement of the failed component marked the achievement of the major objective of the EVA, however, when moving on to other tasks, the two crew members had to abandon their excursion ahead of time due to a recurrence of a water intrusion in the suit of Tim Kopra. Moving back inside in an orderly fashion, the spacewalkers ended their shortened EVA after four hours and 43 minutes.

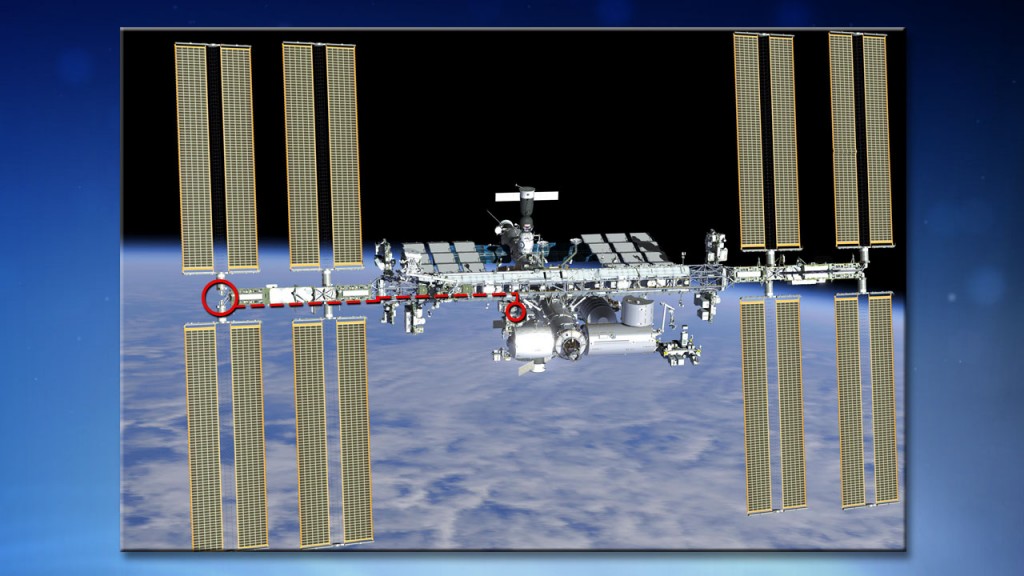

The need for a repair spacewalk arose back on November 13, 2015 when a Remote Bus Isolator inside Direct Current Switching Unit 1 (DCSU) tripped open, indicating a short upstream of the DCSU, specifically in the Sequential Shunt Unit (SSU). Each of the Station’s Solar Array Wings feeds power to an SSU that is responsible for managing the voltage output of the array at a setpoint of 160 Volts by connecting and disconnecting strings of solar cells using 82 capacitors capable of shunting the 82 strings on the array. A regulation of the output voltage is essential for the protection of power system components downstream of the SSU which condition the Station’s eight power channels and distribute power to internal and external systems.

In November, telemetry data indicated a short inside SSU 1B due to a current transient in excess of 2000 Amps that could not be recovered through ground commanding as internal components of the SSU sustained physical damage. The DCSU responded as designed and tripped open, protecting equipment downstream from damage by an overcurrent condition. The trip meant that Power Channel 1B was unavailable and loads normally powered by this channel had to be tied to the 1A channel in order to avoid an extended loss of power to payloads and systems. Although not ideal, ISS can function with seven of its eight power channels but the situation represents a loss of redundancy in the event of another power channel loss.

Because an SSU can not be replaced when the solar array is generating power, a replacement can only be performed during orbital night when no power is coming from the solar cells. Naturally, teams desire to maximize the amount of time available for the replacement and therefore target a period of low beta angles for the repair as this offers the longest possible night duration. In low-beta periods, orbital geometry causes the solar arrays to be illuminated side-on, offering longer periods of darkness. The earliest low-beta period after the November 13 failure was January 12 through 18 leading to the selection of the January 15 EVA date.

The SSU replacement procedure has been completed in orbit once before on the 3A SSU which encountered an initial failure in September 2012 involving only one of its 82 capacitors from which the unit was recovered without the need for replacement. A second, more severe, overcurrent event occurred on this SSU in May 2014 requiring a replacement EVA that was performed five months later, restoring full functionality of the system.

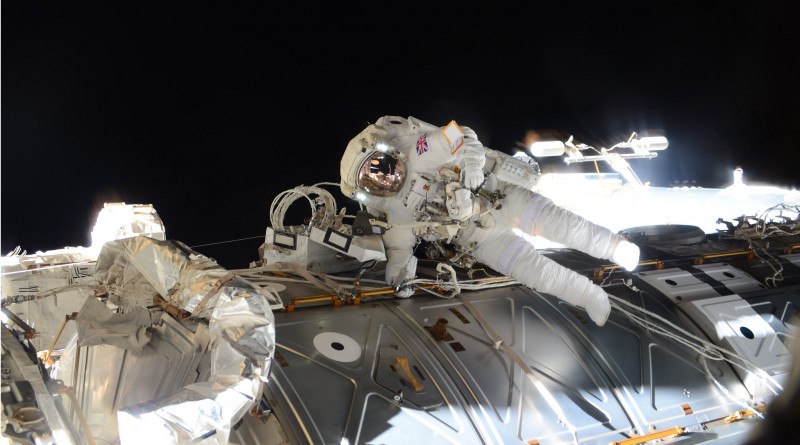

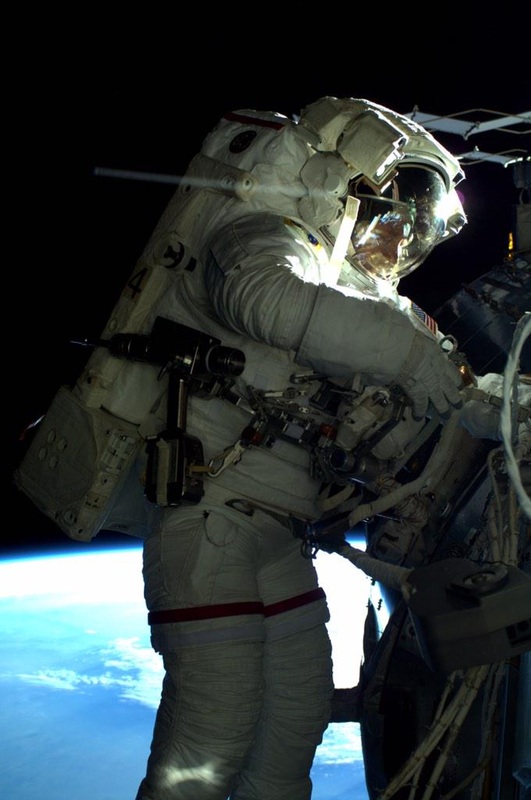

Friday’s spacewalk, U.S. EVA-35, started at 12:48 UTC with NASA’s Tim Kopra designated the lead spacewalker, EV-1, embarking on his third career EVA, and ESA’s Tim Peake, EV-2, making his first walk in space. Climbing out of the airlock, Tim Peake marked the first time in history that a UK national embarked on a spacewalk – his suit adorned with a Union Jack in a historic first after UK-born astronauts conducted EVAs as NASA Astronauts with U.S. flags on their suits.

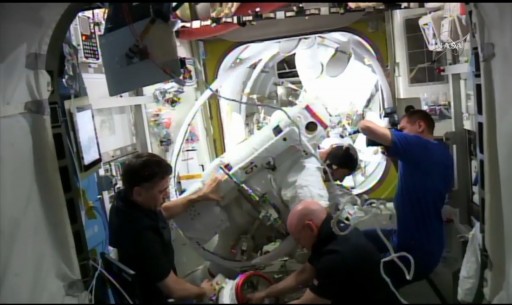

The two crew members were sent outside by Scott Kelly who was in charge of preparing their suits and the airlock for the day’s operation, going through detailed checkouts of the two EMUs and a two-hour pre-breathe protocol to remove nitrogen from the spacewalkers’ blood. At Mission Control in Houston, Reid Wiseman was ready to take over as EVA Capcom, choreographing the spacewalk from the ground. Wiseman had personal experience with the task at hand since he was involved in the SSU-3A replacement one and a half years ago.

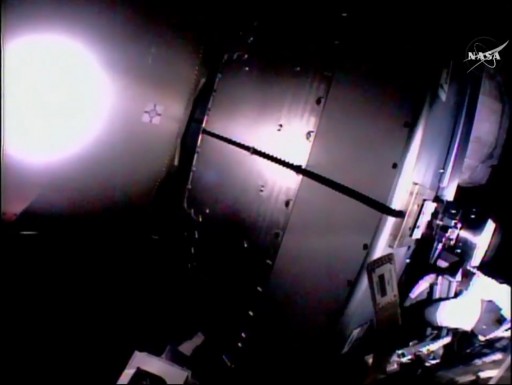

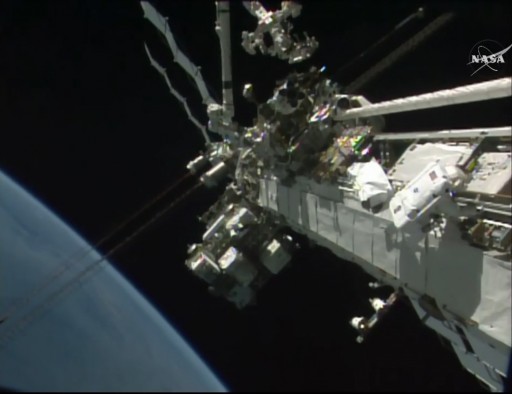

Upon egressing the airlock and completing the prescribed checks of their space suits, the two crew members began translating all the way to the outermost Starboard Truss Segment, S6, where the failed SSU was located. Along the way, Tim Kopra picked up an Articulating Portable Foot Restraint (APFR) that was then set up at the worksite to provide a stable base for Kopra to allow him to use both hands for the SSU replacement.

The entire spacewalk was set up around one particular 31-minute orbital night with sufficient time budgeted beforehand to allow the crew to set up for the removal of the old SSU and the installation of the spare part which had been stored aboard ISS since 1999 and was put through testing in the weeks leading up to Friday’s excursion.

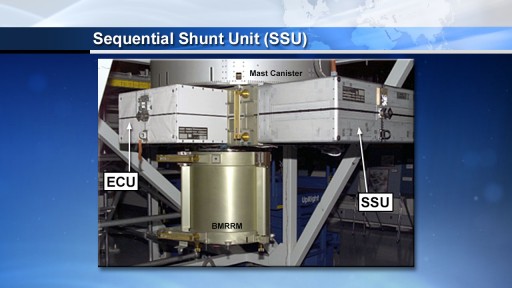

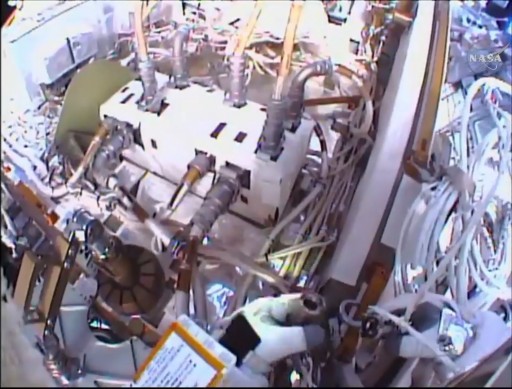

The Sequential Shunt Unit is a rectangular box weighing in at 100 Kilograms. It is installed on the base of the Mast Canister Assembly of the Solar Array Wing and features blind-mate connectors on its base plate that automatically engage when the box is locked in its precise position – making use of guide rails and a single attachment bolt.

While still in daylight, Tim Kopra used a ratchet wrench to break torque on the single Acme Bolt holding the SSU in place. He was instructed to make no more than one turn on the bolt to ensure the connectors at the base remained in physical contact to avoid electrical arcing. Tim Peake readied the spare SSU, releasing straps holding it inside its equipment bag. Kopra made sure his Pistol Grip Tool was ready and the duo then had the opportunity of taking a few photos as they had to wait for night to set in.

Once the sun had set, Mission Control confirmed that the solar array was no longer generating power, giving the crew a GO to begin a race against the clock as they only had half an hour of darkness to remove the failed SSU and put the new one in position. In case of any bigger problems taking up too much time, the crew was instructed to safe the worksite ahead of sunrise and re-attempt the R/R during a subsequent eclipse.

The two Tims made quick work removing the SSU by fully releasing the bolt using the Pistol Grip Tool and sliding the box out. Peake was able to complete a visual inspection of the failed unit, showing no external damage and confirming that the fault lies within the SSU. The failed SSU was temp-stowed using a Scoop installed on it during the preparatory steps.

Next, Peake handed the spare SSU to Kopra and guided it into a good position with proper alignment since no soft-dock feature exists for the SSU. Kopra made use of the wrench to tighten the bolt with the PGT coming to use for a final torquing of the bolt to mark the completion of the SSU replacement with plenty of time to spare.

After the new unit was put in place, an initial sign of trouble emerged on Kopra’s space suit in the form of an off-nominal carbon dioxide reading. The CO2 sensors within the EMUs are known to fail when coming into contact with moisture for example sweat. Reviewing data, Mission Control decided to press on with the EVA and instructed Kopra to pay attention to possible CO2 symptoms as part of the standard procedure in case of a sensor problem.

A little over two hours into the EVA, the spacewalkers began cleaning up the worksite – packing the removed SSU into its bag, taking engineering photos and removing the foot restraint. Once the sun was up, Mission Control was able to verify that the Sequential Shunt Unit was operating as expected, marking a successful restoration of the Station’s eighth power channel and returning the Power System to a fully functional configuration.

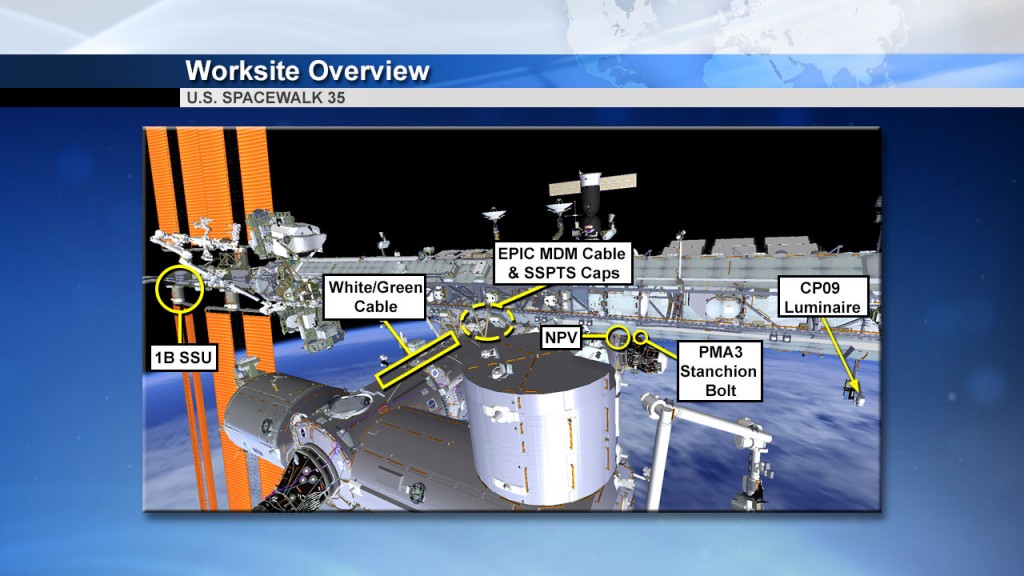

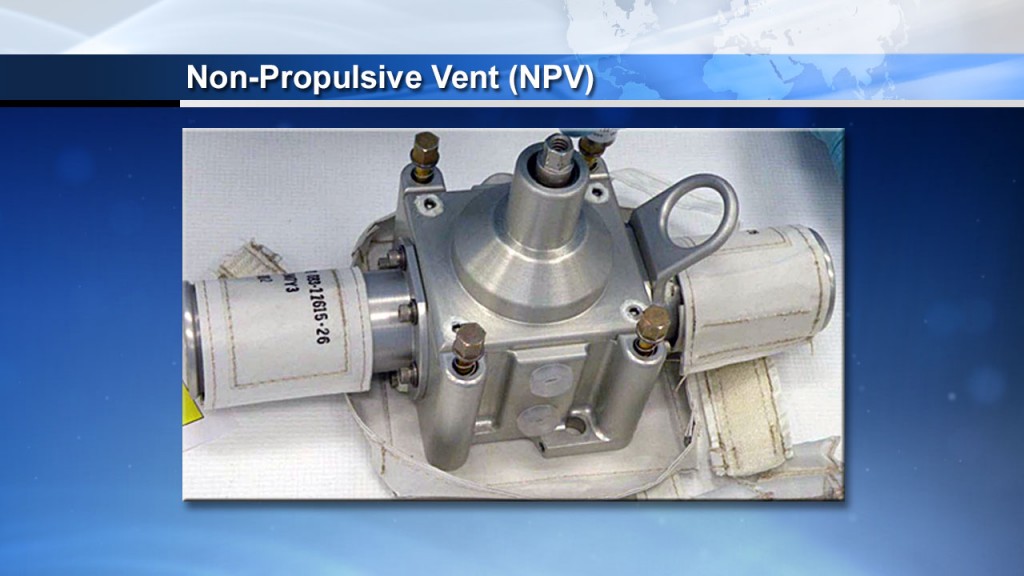

Moving back inboard, Tim Peake stowed the removed SSU inside the airlock to ensure it would be aboard ISS for a future return to Earth to be inspected by specialists and possibly be refurbished for future use as only one spare remained on ISS and one functional unit was on the ground for launch when needed. Checking off the primary objective of the EVA, the two crew members parted ways to start working some tasks from the EVA to-do list, specifically the installation of a Non-Propulsive Vent on Node 3 and the routing of electrical and data cables.

Tim Kopra dropped a bag of cables off port of the Z1 truss and headed on to Node 3 to install the Non-Propulsive Vent (NPV). The NPV allows atmospheric waste gases to be released overboard without applying a propulsive force which would be a problem for ISS attitude control. The Node 3 NPV was removed prior to last May’s relocation of the Permanent Multipurpose Module because of extremely tight clearances for the robotic move of the PMM. Also faced with tight clearances, Kopra had to remove a cover plate before putting the NPV into a soft-docked position and tightening a subset of its structural bolts. Kopra then headed to Pressurized Mating Adapter-3 (PMA-3) to remove a launch restraint in order to free up some cables that need to be disconnected during a future EVA in preparation for the relocation of PMA-3 to Node 2 for future Visiting Vehicle Dockings.

Meanwhile, the other Tim worked another tedious cable working task, many of which had been part of recent EVAs to set up for future Commercial Crew Vehicle traffic. Peake started on the Nadir Side of the Destiny lab to deploy an International Docking Adapter (IDA) cable reel – one leg of which was to be routed aft to a Node 1 connector panel while the other was routed to the infamous ‘rats nest’ on the Port side of the Z1 truss where many cables and connector panels are located, creating a complex worksite for crew members tasked with electrical work. Peake connected the cable to the pre-staged data cable left by Tim Kopra.

His remaining tasks were to connect the EPIC MDM data cable to the Multipurpose Laboratory Module Ethernet Cable on Node 1 to provide data connectivity to the MLM once launched in the coming years. Also, Peake was to route the final cable leg to Node 2 to be stowed there in preparation for the arrival of PMA-3 and IDA-3 on the zenith side of the module.

Tim Kopra – after finishing work with the NPV – reported a water accumulation inside his helmet, not nearly as serious as the water intrusion experienced by Astronaut Luca Parmitano in 2013 but with the obvious potential to escalate into a similar situation. Mission Control, making use of lessons learned from the 2013 mishap, quickly called an EVA Termination – an orderly end of the EVA that allows the crew to safe their worksites, head back into the airlock and complete a nominal repressuriation as opposed to an EVA Abort which would see the immediate return to the airlock and an emergency repressurization.

Initially reported to be the size of a golf ball, the water accumulation inside Kopra’s helmet grew in size and could be seen from the outside by Tim Peake. Kopra was first to ingress the airlock so that Scott Kelly could move him inside the Equipment Lock first and make sure his helmet came off as quickly as possible. The team went through an orderly repressurization, marking the end of the EVA after four hours and 43 minutes.

Once the airlock was repressurized, Kelly opened the internal hatch and moved Kopra to the Equipment Lock, assisted by Russian crew members Yuri Malenchenko and Sergei Volkov. Kelly used a syringe to collect some of the water for analysis given the implications of this recurrence of the water intrusion that had been considered at least partially solved after the investigation into the mishap involving Luca Parmitano.

It is not yet known what caused the water to enter Kopra’s helmet and NASA will complete a thorough investigation, also going through testing of the EMU #3011 suit in the coming days. EMU #3011 was also worn by Parmitano during the 2013 EVA but underwent a major overhaul with a number of component replacements including the now infamous Fan-Pump Separator that had become the prime suspect for the water intrusion issue. Kopra reported the water entering his helmet to be cold, further suggesting its origin to be the FPS.

Friday’s EVA was the 192nd in support of ISS Assembly and Maintenance for a total of 1,200 hours. It was Kopra’s third EVA for a total of 13 hours and 31 minutes; Peake’s total stands at 4 hours and 43 minutes. The next ISS EVA will be conducted by Yuri Malenchenko and Sergei Volkov in early February out of the Russian Pirs Airlock.

Fan Pump Separator Situation

Looking back at recent years, ISS had a number of issues with the EMUs starting in 2013 when a serious water leak emerged on Luca Parmitano’s space suit while he was working on the outside of ISS leading to a termination of the spacewalk and Parmitano reaching the safety of ISS just in time with water pooling around his head – covering his eyes, nose and ears when his helmet was taken off by the Station crew.

Through on-orbit testing and troubleshooting, teams traced the problem back to the Fan Pump Separator – a critical component that circulates oxygen through the suit while its pump transports the coolant fluid and the water separator removes water from the ventilation loop to condition the air that is returned to the crew member via the T2 port of the helmet. A detailed study was conducted to trace back the issue and NASA identified a rather complex mechanism that led to the failure of the EMU’s Fan Pump Separator due to a build up of silica contamination that originated within water support system of ISS that is regularly used to flush and replenish the water cooling system of the suits.

As a corrective measure, NASA developed new EMU servicing procedures including regular water sampling and more frequent water loop scrubs and filter replacements.

However, despite the elimination of what was thought to have been the root cause of the Fan Pump Separator issue, problems with the component and other suit parts continued to take up the crew’s time who often spent entire days inside the airlock performing suit maintenance. The Dragon SpX-3 mission delivered the #3003 suit to ISS and returned EMU #3015 to Earth after it exhibited issues with its sublimator and telemetry systems.In October 2014, the Fan Pump Separator of EMU #3005 failed to spin up during an EMU Loop Scrub. After the FPS seized up on start, it was removed from the suit and replaced by a spare in December.

In January 2015, EMU #3011 showed a failure when attempting to re-start its Fan Pump Separator and troubleshooting could not recover the system. This required EMUs to be switched for a set of three EVAs that were conducted in February and March by Terry Virts and Barry Wilmore who used EMUs #3003 and #3005. The problematic FPS from the #3011 suit was returned to Earth by Dragon SpX-5 for detailed testing and further study of the ongoing issues with this particular component that had been in use for many years on the current EMU design.

In April, the crew went through a lengthy operation to swap the Hard Upper Torso sections of EMU’s #3005 and #3010 so that #3010 would become a size XL suit. EMUs #3003 (Size L) and the #3010 suit were considered the primary space suits with EMU #3005 as a backup.

However, during a regular test in late May, EMU #3010 showed insufficient cooling water flow due to an apparent problem with its Fan Pump Separator that had been installed on this suit since May 2014. Given the trouble with the Fan Pump Separators on all space suits on ISS, NASA continues to investigate the potential causes with great interest. The failed FPS was removed from EMU #3010 in early June and returned to Earth aboard the Soyuz TMA-15M spacecraft.

Originally planned for EVA-34 in December were EMUs #3010 and #3003 – both had been in use for EVAs 32 and 33 and showed no issues. On Saturday, during preparation for Monday’s excursion, the fan of EMU #3003 failed to start up and the suit was replaced by #3011 requiring the crew to switch batteries, MetOx containers as well as the EVA arms and legs from #3003 to #3011 to provide the correct suit size for Tim Kopra. Because #3011 had a fresh Fan-Pump-Separator, it was considered the best option for this spacewalk and no issues with the suit were observed during EVA-34.

A newly refurbished suit (#3008) arrived aboard the Cygnus OA-4 mission and was readied for use by Tim Peake with an additional fit check confirming the size of the suit. Both suits underwent water loop servicing and checkouts prior to Friday’s EVA-35.

Although there was no prior indication of any danger for water intrusions into the space suit from the FPS, the usual precautionary measures were taken by Kopra and Peake, notably the snorkel in the space suit that could be used in case water enters the helmet, and the Helmet Absorption Pads that were checked multiple times during the EVA to ensure no water is being absorbed by it.

Kopra did not have to use the snorkel and remained in a relatively comfortable situation until ingressing the airlock, unlike Luca Parmitano who was facing a much larger quantity of water inside his helmet, covering his ears, eyes and nose.