NASA’s RapidScat Ocean Wind Sensor ends Operations at Space Station

NASA’s RapidScat instrument hosted outside the International Space Station has ended its mission of measuring winds over the world’s oceans after suffering a power failure earlier this year – just before reaching its planned two-year mission duration.

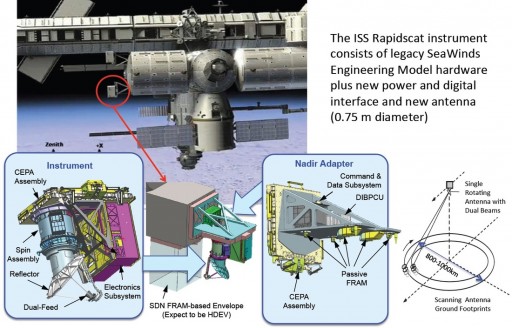

RapidScat was the first continuous Earth-observing instrument specifically designed to operate on the International Space Station. The project was born out of necessity as a replacement for an ocean wind-sensing instrument on the aging QuikScat satellite which had shown signs of severe degradation in 2009. Because a dedicated satellite could not be built for budgetary and schedule reasons, NASA decided to pull the QuikScat engineering model out of storage and fit it for deployment on the Space Station.

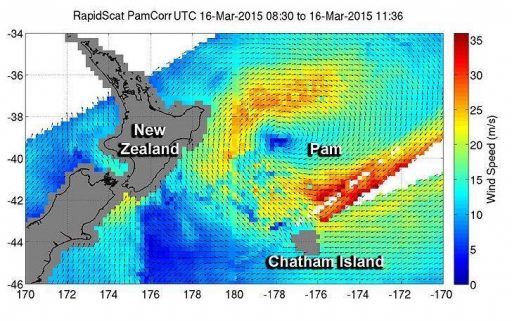

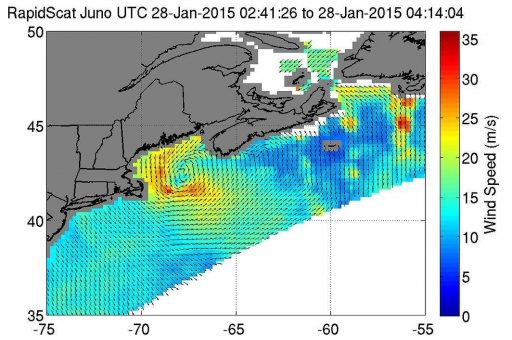

The measurement of ocean winds is of importance to the scientific community but also represents a vital parameter for operational meteorology, specifically forecasting of hurricanes and typhoons – explaining why there was considerable pressure to get a replacement instrument into orbit to continue delivering this crucial piece of data.

RapidScat was realized in less than two years on a shoestring budget of $26 million – not even a tenth of the cost of a dedicated satellite mission. The instrument was launched in September 2014 inside the external payload accommodation of the fourth regular Dragon mission to the Space Station. After Dragon arrived at ISS, the Station’s robots were used to pull RapidScat from the spacecraft’s trunk and install it in its Earth-pointed position on the External Payload Facility of the European Columbus Module.

Within a month of its installation, RapidScat began spinning its antenna and collected measurements of intensifying tropical storms as well as large-scale phenomena including valuable data on changing winds in the Pacific Ocean linked to the 2015/16 El Nino event.

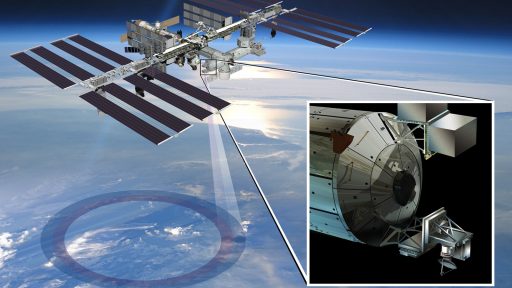

The instrument’s working principle was to bounce microwave pulses off the ground and record the echo reflected from the ocean surface to extract wind speed with an accuracy of 2 meters per second and wind direction accurate to 20 degrees. RapidScat rotated its 75-centimeter antenna dish 20 times per minute to sweep out a circle of 1,100 Kilometers in order to cover a large area of the ocean.

>>Detailed Technical Overview of RapidScat

For nearly two years, the spinning dish of RapidScat was a common sight in video beamed down from the exterior of the International Space Station with measurements only interrupted when spacecraft arrived and departed the orbiting complex.

The RapidScat instrument stopped working on August 19, 2016 after a power anomaly.

The August 19 anomaly first presented itself as an outage of one of two power supply units delivering power to the external payloads of Columbus, resulting in a loss of power to RapidScat, the Solar Monitoring Observatory and the HDEV camera suite. When attempting to re-power RapidScat, the power distribution unit experienced an electrical overload which indicated a more serious issue was present.

RapidScat was isolated and ground teams were able to restore power to the other two external payloads, but all attempts to re-activate the RapidScat instrument failed. The payload’s survival heaters, powered through a different string, kept RapidScat alive while engineers continued attempts to restore instrument operations.

A final attempt on October 17 did not bring success and RapidScat was declared failed for good, marking the conclusion of a successful stop-gap mission. NASA issued a statement this week confirming the end of the RapidScat mission.

“As a first-of-its-kind mission, ISS-RapidScat proved successful in providing researchers and forecasters with a low-cost eye on winds over remote areas of Earth’s oceans,” said Michael Freilich, director of NASA’s Earth Science Division. “The data from ISS-RapidScat will help researchers contribute to an improved understanding of fundamental weather and climate processes, such as how tropical weather systems form and evolve.”

Although RapidScat did not quite reach its desired two-year mission duration, the timing of its deployment could not have been better. The QuikScat scatterometer stopped functioning in 2009, but forecasters still had access to data from a similar instrument on India’s OceanSat 2 satellite. When it stopped functioning in early 2014, RapidScat was almost ready for launch to ISS – keeping the gap in ocean wind data to only a few months instead of several years had a full-scale satellite mission been chosen as a QuikScat successor.

NASA currently has no plans to launch another scatterometer mission and the U.S. is now again relying on data provided by India following the successful launch of the ScatSat-1 satellite in September. However, ScatSat data can only partially mitigate RapidScat’s loss as it resides in a polar orbit from where the spacecraft can monitor global wind patterns but overflies each location at the same time every day. The ISS orbit offered a look at ocean wind dynamics at different times of day and also provided a better revisit rate for mid-latitudes.

“The unique coverage of ISS-RapidScat allowed us to see the rate of change or evolution in key wind features along mid-latitude storm tracks, which happen to intersect major shipping routes,” said Paul Chang, Ocean Surface Winds Science team lead at NOAA’s Center for Satellite Applications and Research. “ISS-RapidScat observations improved situational awareness of marine weather conditions, which aid optimal ship routing and hazard avoidance, and marine forecasts and warnings.”

The latest logistics planning documents from the International Space Station Program show RapidScat being removed from Columbus in the second half of 2017 to be disposed of via destructive re-entry over the Pacific Ocean, packed into the trunk of the Dragon SpX-13 cargo craft.

The success of RapidScat as a long-term Earth Observation instrument hosted on ISS inspired other projects to look into using the Station as an observation perch, circling the Earth in a 400-Kilometer orbit. The Cloud-Aerosol Transport System (CATS) has been in operation since early 2015 to measure atmospheric aerosols and clouds and two more instruments are expected to take up residence on ISS in 2017, one looking at Earth’s ozone layer, the other studying lightning over the tropics and mid-latitudes.