Falcon 9’s Light-Lift Mission Places Taiwan’s FormoSat-5 into Orbit, 1st Stage Recovered at Sea

A very lightly-loaded Falcon 9 departed its Pacific Coast launch pad on Thursday, carrying into orbit the FormoSat-5 Earth Observation Satellite for Taiwan’s National Space Organization – a contract left over from SpaceX’s Falcon 1 days that ended up creating the most colossal waste of rocket performance in recent history.

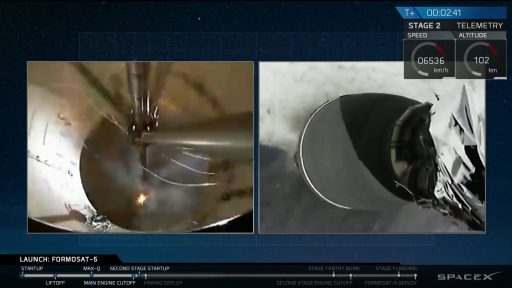

Making its 40th orbital delivery, Falcon 9 lifted off from Vandenberg’s Space Launch Complex 4E at 18:51 UTC, thundering off on an unusual mission that only required one twentieth of the vehicle’s potential performance to the target orbit of 720 Kilometers. The rocket fired its first stage for two minutes and 28 seconds before the second stage took over for a six-and-a-half-minute burn to directly inject the 475-Kilogram satellite into its target orbit – foregoing the more efficient way of a two-burn flight profile that would be in play for a heavier delivery due to fuel requirements. FormoSat-5 sailed off eleven minutes after launch, beginning a mission of at least five years collecting Earth imagery for use by the Taiwanese government.

With plenty of surplus performance on this flight, SpaceX had the opportunity of bringing the first stage back to an on-shore landing, but for reasons that have not been communicated to the public, opted for a powered landing on the Autonomous Spaceport Drone Ship ‘Just Read The Instructions’. Arising from the mission’s lofted trajectory, the first stage had the longest ‘hang time’ to date, climbing to 247 Kilometers before falling back toward Earth, successfully touching down on its four fold-out landing legs just shy of eleven minutes after liftoff.

The lofted trajectory of Thursday’s mission also afforded a favorable opportunity for returning the rocket’s payload fairing halves – a feat SpaceX aims to master by the end of this year to further reduce the cost of its launch vehicles.

Thursday’s launch was the fortieth flight of the Falcon 9 rocket since its inauguration in 2010, the fifth from its West Coast launch site, the 20th in the Full Thrust Configuration and the 12th in 2017 that is already the busiest year on record for the California-based company. The landing of Booster #1038 brought SpaceX’s record to 15 successful first stage landings out of 20 attempts; it was the ninth successful drone ship landing and brings SpaceX’s streak of consecutive landing successes to eleven.

FormoSat-5 has been on SpaceX’s launch manifest since 2010 when the National Space Organization of Taiwan signed with the company for $23 million, booking the satellite on a Falcon 1e launch vehicle SpaceX expected to put on the market in 2011. However, the company withdrew the Falcon 1 altogether after five launches in order to focus on the larger Falcon 9 vehicle, also skipping the earlier proposed Falcon 5.

This meant that satellites originally assigned to Falcon 1s would move to Falcon 9 which, in some cases like Orbcomm, allowed satellites that were to launch one at a time to be grouped together to take advantage of the higher performance of the Falcon 9.

However, FormoSat-5 as a stand-alone project, remained as a solo passenger – initially aiming for a late 2013 liftoff but ending up with significant delays due to technical challenges encountered in satellite development. FormoSat-5 was reported in launch readiness in May 2016, but remained grounded as SpaceX placed priority on other commercial missions that were facing more severe consequences from further delays. This additional delay came with a 10% penalty for SpaceX and the company also lost Spaceflight Industries’ SHERPA space tug that had been placed on the launch as a co-passenger until opting out in early 2017 due to the uncertainty associated with the mission’s launch date.

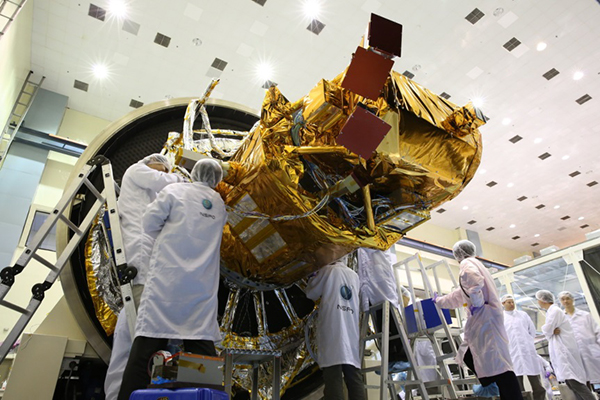

Finally reaching the launch pad, FormoSat-5 is becoming Taiwan’s first domestic-built satellite after NSPO relied on outside contractors for previous FormoSat missions. The project was initiated in 2005 as a follow-on to the FormoSat-2 spacecraft that launched as Taiwan’s prime Earth Observer in 2004 and continued operating until being placed into retirement last year. FormoSat-5 is expected to close a year-long gap in remote sensing data availability and significantly expand on the previous mission’s capabilities.

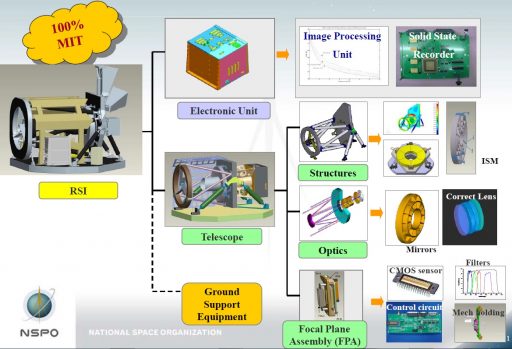

FormoSat-5 carries a pair of instruments, the Remote Sensing Imager is the mission’s primary payload for the collection of remote sensing data and an Advanced Ionospheric Probe will measure Earth’s plasma environment for ionospheric research, space weather studies and geophysical research looking into the prediction of earthquakes through an ionospheric response triggered by tectonic plate movement.

The Remote Sensing Imager hosts a 45-centimeter telescope feeding a multi-band line detector array, capable of capturing black-and-white imagery with a ground resolution of two meters and multi-spectral images in four bands with a resolution of four meters. Imagery captured by the instrument will be used in a number of areas including environmental monitoring, national security, disaster relief and a variety of scientific areas.

The Advanced Ionospheric Probe combines a series of sensors in a compact package installed to face the satellite’s direction of travel to experience the inflow of charged particles that will be measured with high spatial resolution to deliver detailed maps of Earth’s ionosphere to monitor seasonal, space-weather induced and geophysical effects on Earth’s particle environment.

>>FormoSat-5 Satellite & Instrument Overview

Weighing in at 475 Kilograms and standing 2.8 meters tall, FormoSat-5 filled only a small portion of Falcon 9’s standard 13-meter tall, 5.2m diameter payload fairing. Performance-wise, Falcon 9 can be considered several sizes too large for a mission such as this and SpaceX is taking a financial hit considering the company currently offers Falcon 9 for $62 million and only raked in around $21 million for this mission. Nevertheless, at the time the FormoSat-5 contract was signed, it represented critical business for SpaceX and helped the company over initial struggles with Falcon 1 and on to the successful Falcon 9 project.

Continuing at a decent launch pace, Thursday’s flight came only ten days after Falcon 9 last flew when lifting the Dragon SpX-12 spacecraft into orbit for a cargo-delivery mission to the International Space Station. Falcon 9 #40 went through its static fire test on Saturday and returned to the hangar next to SLC-4E to meet its payload before returning to the sea-side launch pad in preparation for a lengthy countdown.

Falcon 9 went through a detailed checkout campaign while still enshrouded in the dark of night to receive a clean bill of health with all subsystems tested thoroughly before pressing into the tail end of the count, setting up for a 42-minute launch window. Engineers cleared the pad and Launch Controllers were polled at L-67 minutes, reporting a unanimous ‘go’ to proceed with the fully automated propellant loading sequence.

As clocks entered the final hour of the count, Falcon 9 started the highly choreographed tanking operation – starting with loading the two-stage vehicle with around 155 metric tons of Rocket Propellant 1, chilled to -7°C. RP-1 entered its pre-topping targets inside T-30 minutes with final top-up performed inside T-6 minutes to deal with thermal expansion of the densified propellant. Loading of 360 metric tons of sub-cooled Liquid Oxygen at -207°C started at T-35 minutes on the first stage and T-20 minutes on the second stage with topping level reached right at the T-2-minute mark to ensure flight mass is achieved as close to liftoff as possible to avoid LOX warming up inside the tanks.

The 70-meter tall rocket headed into final preparatory steps at T-7 minutes, starting to chill down its engines in preparation for ignition. Final tests were underway on the rocket’s engine valves and actuators while the tanks were pressurized to allow the Strongback structure to move back to its launch position. Falcon 9 switched to internal power, armed its autonomous Flight Termination System and assumed control of the countdown at T-1 minute, overseeing the final pressurization of tanks to lead up to ignition at T-3 seconds.

The characteristic green flame of Falcon’s igniter mixture erupted from the business end of the rocket as the nine Merlin 1D engines ramped up to a liftoff thrust of nearly 700 metric-ton-force, lifting Falcon 9 off the ground to embark on a long-delayed mission. Powering away from the Californian coast line, Falcon 9 turned to the south-west – aiming to deploy the satellite into a Sun Synchronous Orbit.

Given the abundance of performance on this mission, Falcon 9 was flying a direct injection profile, targeting to deploy the FormoSat-5 satellite into a 720-Kilometer orbit, inclined 98.28 degrees. Typically, missions into higher circular orbits would use two upper stage burns as seen on SpaceX’s recent deliveries for Iridium that feature an initial boost phase into an elliptical orbit followed by circularization 625 Kilometers in altitude at the high point of the orbit.

A direct delivery eliminates the risk of the additional engine re-start and longer mission duration and is therefore chosen whenever possible. To facilitate FormoSat’s delivery, Falcon 9 was programmed to fly an extremely lofted trajectory comprising a steep initial ascent to the target altitude and then accelerating to the desired circular orbit velocity.

Racing into clear skies after emerging from the typical Vandenberg fog, Falcon 9 passed Mach 1 barely over a minute into the flight and encountered Maximum Dynamic Pressure 69 seconds into the flight, throttling back for a brief moment to reduce stress on the ascending vehicle. Guzzling down 2,500 Kilograms of propellant per second, Falcon 9 passed 40 Kilometers in altitude two minutes into the mission, gearing up for the critical staging sequence.

MECO – Main Engine Cutoff – was marked at T+2 minutes and 28 seconds after the first stage accelerated the vehicle to a speed of 1.89 Kilometers per second. Illustrating the initial drive to increase altitude before focusing on building speed, the two stages parted ways four seconds after MECO at an altitude of 89 Kilometers with the second stage moving into start-up mode for ignition another seven seconds later and the first stage heading into post-separation maneuvers.

Due to this particular mission’s profile, the first stage was in for a longer ride, coasting uphill for three minutes after separation before beginning to fall back toward Earth. While flying outside the atmosphere, the booster used its cold gas thrusters to maintain stable body rates and re-orient for entry.

With the drone ship parked 344 Kilometers from the launch site, no boostback was performed and the vehicle continued on a ballistic arc until firing up for the entry burn.

Given the lofted trajectory, the first stage was expected to have the longest flight time from liftoff to touchdown of any previous Falcon 9 launch. Falling back to Earth, the 47-meter long booster accelerated to a peak speed around 2.4 Kilometers per hour.

The booster fired up three engines at T+8 minutes and 47 seconds to slow down prior to encountering the dense layers of the atmosphere, also providing a trajectory correction to aim the booster toward the drone ship. The 38-second entry burn slowed the stage to under 870m/s and was followed by a 55-second long descent through the atmosphere with the booster’s four grid fins providing three-axis control and modifying the booster’s angle of attack to steer it to the drone ship.

Stage 1 went through the transsonic region and lit up its center engine half a minute before touchdown to arrest its vertical speed and come to a gentle landing on the drone ship’s deck. The four landing legs deployed in the last seconds of the descent and the booster made a bulls-eye landing at T+10:48 just 0.7 meters from the target center, reimbursing SpaceX for some of the money lost on this mission since Booster #1038 is a prime candidate for re-flight.

Another re-use element in Thursday’s mission was the payload fairing which SpaceX hopes to make re-usable sooner rather than later since it represents a considerable fraction of Falcon’s launch price. The fairing comes at around $5 million apiece and is a composite structure that requires a fairly lengthy manufacturing process – creating a potential future bottle neck if SpaceX continues to step up its launch pace.

An initial attempt of returning the fairing halves intact came on the SES-10 mission and managed to return one fairing half mostly undamaged and the BulgariaSat-1 mission in June managed to return both halves practically intact. To make the fairings reusable, SpaceX adds a thruster system that stabilizes the clamshell-half in a favorable orientation for re-entry and steering chutes guide each fairing half to a pre-determined recovery location – either via splashdown in the ocean or aerial recovery.

Thursday’s flight provided an excellent opportunity for fairing recovery due to the lofted trajectory that allowed the fairing to separate while the rocket was not traveling as fast as it would for a GTO launch or typical LEO mission. Separation of the fairing was confirmed two minutes and 58 seconds into the launch when Falcon 9 was 132 Kilometers in altitude, traveling 1.81 Kilometers per second. The outcome of the recovery attempt was not shared in real time.

While the first stage enjoyed its record-setting sub-orbital arc, Stage 2 fired its 95,000-Kilogram force MVac engine for a planned burn of six minutes and 38 seconds, initially continuing a steep climb until pitching down to focus on building speed to reach the target orbit. Shutdown occurred nine minutes and 18 seconds into the flight and orbital parameters were reported as nominal by SpaceX launch controllers.

FormoSat-5 was pushed off by loaded springs eleven minutes after launch, sailing off on a mission of at least five years – earning SpaceX its 12th check mark of the year. For the second stage, the day was not done at spacecraft separation, set for over one orbit of coasting prior to a retrograde deorbit maneuver to set up for destructive re-entry over the South Pacific around two hours after launch, aiming for a zone west of New Zealand.

SpaceX will be in action again on September 7 with the launch of the fifth X-37B mission for the U.S. Air Force from the Kennedy Space Center. The company’s next west coast launch is lined up for late September with the next batch of Iridium-NEXT communications satellites.