Juno Spacecraft enters Safe Mode, Loses valuable Science on close Jupiter Pass

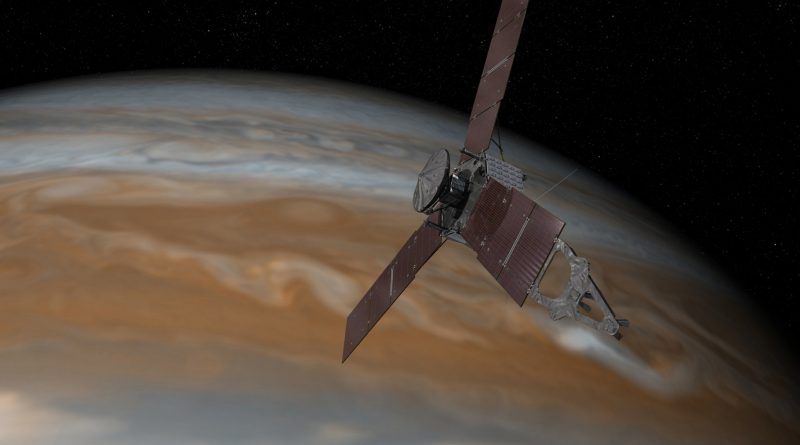

NASA’s Juno spacecraft – currently in a highly elongated orbit around Gas Giant Jupiter – unexpectedly entered safe mode on Wednesday preventing its scientific instruments from capturing data when the spacecraft made its second close orbital brush past the planet later in the day, flying around 4,200 Kilometers above the dense cloud tops of the Jovian atmosphere.

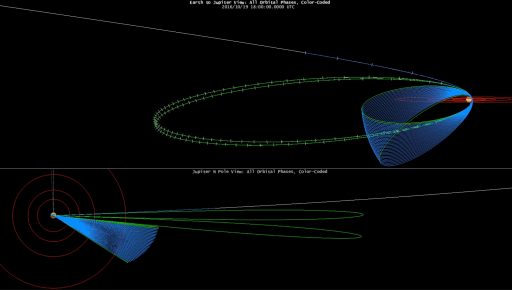

The Juno team announced last week that a large orbital adjustment originally planned for this low pass had to be postponed due to a suspicious signature seen on a pair of propulsion system valves – warranting additional study. As a result of the delay, Juno was to remain in its 53.5-day Capture Orbit for at least one more lap around the planet, freeing Wednesday’s close pass up for a full cycle of science operations that can only occur around the perijove-passage when Juno is at close distance to the planet.

According to a NASA statement, the unexpected safe mode was triggered at 5:47 UTC on Wednesday due to a software performance monitor inducing a reboot of the central computer of the spacecraft. In response to the re-start, Juno transitioned to safe mode in which all science instruments are deactivated, causing the mission to miss its perijove 2 science pass. After the event, high data-rate communications were restored and Juno was switched to a diagnostics mode to look into the flight software issue responsible for the safe mode.

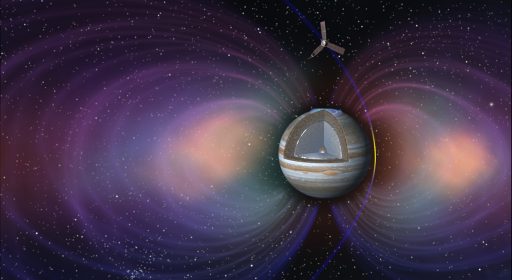

At the time the safe mode was triggered, Juno was still over 13 hours from the time of its closest approach, still at some distance to the planet’s intense radiation belts and magnetic fields which are one of the biggest concerns of the mission when looking at possible electronics upsets and overall degradation.

Teams are currently working through a standard recovery procedure that ensures the spacecraft is kept safe while the anomaly is being diagnosed to prevent future occurrences from taking away additional science passes. Because of Juno’s limited lifetime in Jupiter’s radiation environment, losing a science pass hurts the mission more than others since the current plan only foresees 36 closes passes for the primary missions with only a short extension possible should Juno be able to weather the extreme radiation.

While Juno remains in a stable, power-positive configuration, the Mission Team is now facing two unrelated issues both of which need resolution prior to the next close pass by Jupiter on December 11.

Last week, two Helium check valves were found to be opening much slower than expected which prompted the postponement of the Period Reduction Maneuver designed to reduce Juno’s orbital period from 53.5-days to a two-week orbit for regular science operations.

The two check valves are responsible for directing Helium flow to the spacecraft’s fuel and oxidizer tanks to keep them at the required pressure levels for operation of the pressure-fed LEROS-1B main engine. They also ensure that no reverse flow is possible, preventing gaseous propellant residuals from migrating into the pressurization system.

The Period Reduction Maneuver represents the last planned use of Juno’s bipropellant propulsion system.

The advantage of still having Juno in the elliptical Capture Orbit is that it gives the team several weeks to deal with the two issues ahead of the next close pass and also keeps Juno at a safe distance to the powerful radiation belts.

Downplaying the current issue, Juno’s Principal Investigator Scott Bolton said on Wednesday no science would be lost if the spacecraft remained in a 53.5-day orbit – it would simply take longer to capture the mission’s desired data set.

However, the collection of data from 35 perijove passages as required by the science team would create a mission duration of over five years and it is doubtful Juno could survive that long – even if staying away from the most intense radiation belts throughout its flight.

This is not the first safe mode situation encountered during the Juno mission. During the 2013 Earth Flyby, Juno went into safe mode twice – in the close phase of the gravity-assist and the next time a few days later. Both were caused by minor issues, but provided hands-on experience to the mission team, working out minor kinks with the spacecraft which will certainly be helpful in the current situation, dealing with issues while ensuring all core systems remain in a stable configuration.

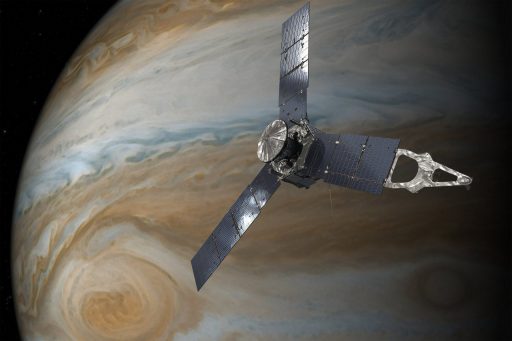

While the Mission Ops Team deals with the two issues on the spacecraft and mission re-planning caused by the missed engine burn, the science team has been working diligently sifting through data collected during Juno’s first close orbital brush past Jupiter back on August 27.

Juno’s Microwave Radiometer, capable of peering 400 Kilometers below Jupiter’s cloud tops, revealed that the prominent belts of orange and white gas masses also exist below the uppermost layer of clouds, but there appear to be some changes with increasing depth the science team currently tries to understand.

The Juno Team also put the finishing touches on the JunoCam data pipeline, allowing the public to access and process data from the mission’s sole imaging instrument. JunoCam largely relies on citizen scientists for processing raw image data into finished image products and so far, results are very promising according to JunoCam’s operators. Raw and processed images can be seen on the Mission Juno Website of the Southwest Research Institute.