Zuma’s Potential Identity

Zuma is a code-named mission of the U.S. Government launching atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in November 2017. Also known as Mission 1390, the project involves Northrop Grumman as the launch procurement agent and possibly also as spacecraft prime contractor for an unnamed Government Agency responsible for the project.

Zuma is the most secretive U.S. space mission in recent memory, only showing up on launch schedules one month in advance of liftoff with very little to no information on the satellite’s identity and role within the U.S. government’s space fleet coming forward before the craft’s secretive liftoff. The existence of the mission on the 2017 launch manifest only became known after SpaceX filed documentation with the Federal Communications Commission on October 13, 2017.

After the existence of the mission became known, some bits and pieces of information began trickling through as space journalists began shaking the tree with the usual suspects, first and foremost the National Reconnaissance Office, operator of the U.S. spy satellite fleet.

Responding to questions from Aviation Week, the NRO stated the Zuma spacecraft “does not belong to the NRO”. Still, confirmation of Zuma being a U.S. Government spacecraft was provided by multiple outlets and Northrop Grumman was identified as the launch procurement agent and satellite provider.

The launch was procured from SpaceX as a standard commercial launch contract, but how exactly the November 2017 liftoff came to be is unknown. Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems signed a launch contract with SpaceX for an unnamed payload in 2015, but no dates were ever assigned to that mission. When Zuma showed up on the schedules, credible sources on Reddit stated that the mission was given priority because of its criticality to the customer’s revenue targets.

Whether this is the genuine reason for the swift implementation of the mission or just a cover for classified requirements to have the payload in orbit at this particular time is open for speculation.

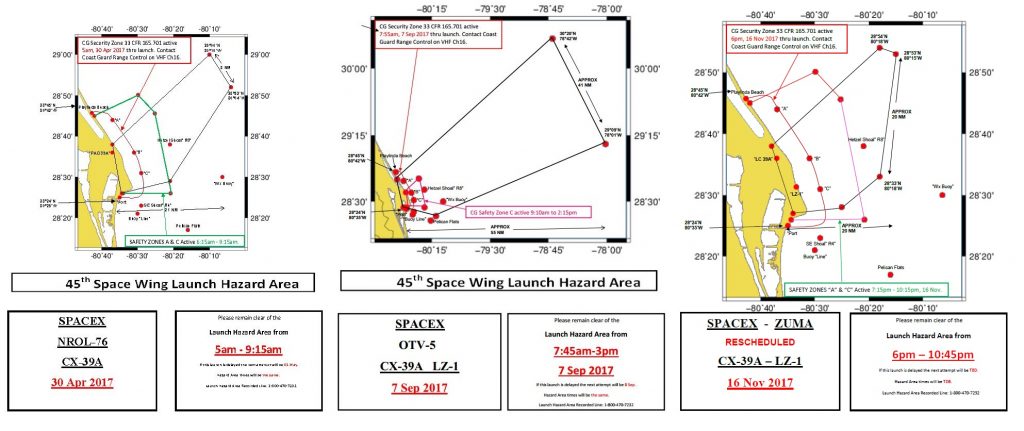

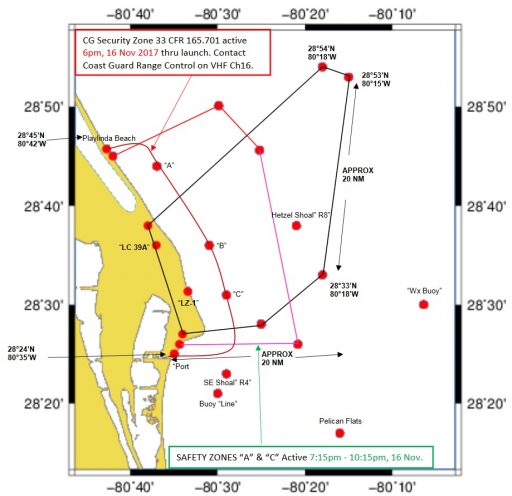

In the days after the surprise mission became known it was also uncovered that Zuma was headed to Low Earth Orbit and the Falcon 9 would make a Return-to-Launch-Site landing at Cape Canaveral’s Landing Zone 1. Range Closures posted for the Zuma mission show Falcon 9 will depart Cape Canaveral to the north-east, suggesting an orbital inclination anywhere between 40 and 60 degrees.

The Launch Hazard Area for Zuma is in the same direction as that of the X-37B OTV-5 and NROL-76 missions launched earlier in 2017 but the area identified for Zuma does not extend that far east as that of OTV-5 – suggesting Falcon 9 will be flying an extremely lofted trajectory that allows the first stage to remain close to Florida’s coast without excessively traveling downrange before reversing course. NROL-76 had closure areas very similar to those for Zuma, only stretching to 80° West.

Looking at the in-flight data, OTV-5 had a MECO velocity of 1,660m/s at an altitude of 65 Kilometers while NROL-76 used a slightly shorter first stage burn with MECO at 1,685m/s and 68km in altitude. Both heading back to Cape Canaveral, the NROL-76 first stage reached a peak altitude of 166 Kilometers, that of OTV-5 peaked at 136 Kilometers – highlighting the differences in lofted flight profiles for two payloads of different launch mass headed to fairly similar orbits.

Performance wise, based on the Launch Hazard area, the Zuma mission appears closer to NROL-76 than OTV-5 with NROL-76 being a curious case itself: the mission appears to have followed a similar contractual process as Zuma. In both cases the launch service was procured by the satellite contractor, Ball Aerospace in the case of NROL-76 and Northrop Grumman for Zuma, though the operators/owners of the two missions appear to be different since the NRO has denied ownership of Zuma.

In terms of contracting, the two missions also appear similar to the mysterious PAN and CLIO satellites that had analysts puzzled in 2009 and 2014.

Both were manufactured by Lockheed Martin and the company also acted as the procurement agent for their launch on behalf of an unknown government agency. Although surrounded by much secrecy, the missions were unusual since photos of both satellites were published ahead of launch, virtually unprecedented for a classified satellite program. The identities of PAN and CLIO were revealed in Snowden Documents as belonging to the NEMESIS Program under direct tasking by the NSA and CIA to provide electronic intelligence collection sites in the sky.

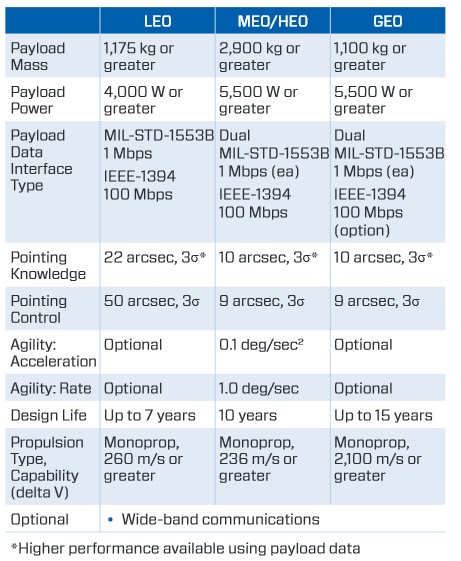

The only spacecraft in Northrop’s catalog justifying a Falcon 9 rocket is the Eagle-3 satellite bus, the highest-performance member of the company’s Eagle product line and available for the entire spectrum of missions for application in Low Earth Orbit, Medium and Highly Elliptical Orbits and Geostationary Orbit. Eagle-3 is designed for high reliability and substantial payload capacity for a wide range of payload types from scientific sensors to communications gear.

Eagle-3 has been conceptualized for longevity and survivability identified as critical design factors, employing a redundant onboard architecture and radiation-hardened electronics. Scalability is also an important aspect for Eagle-3 with a payload mass range of 1,100+ to 2,900+ Kilograms for GEO and MEO missions, respectively.

Eagle-3 supports options for high-agility application for remote sensing and reconnaissance missions, it can support large deployables like communication antennas and supports wide-band communications and low-latency data delivery through high-rate Ka-Band downlink to ground stations or deployed field terminals.

The LEO version of Eagle-3 – the most likely candidate for Zuma – can support payload masses of 1,175 Kilograms upwards, supplies a payload power of 4,000 Watts and supports precise pointing with an attitude knowledge of 22 arcsec and a pointing accuracy of 50 arcsec. The baseline Eagle-3 LEO variant hosts a monopropellant propulsion system using Hydrazine propellant and providing a delta-v capability of 260 meters per second or greater, suitable for missions with frequent maneuvering or regular orbital maintenance needs.

The satellite bus can support payloads with a variety of data needs with communications up to 1Mbps provided by a 1553 data bus and high-rate data up to 100Mbps through a 1394 interface. Eagle-3, in its LEO configuration, supports a nominal design life of seven years.

The mission carried out by Zuma could vary from an operational intelligence-gathering mission (e.g. image or radar collection or as a low-orbiting ELINT satellite) to a USA-193-type technology demonstration. USA-276 (NROL-76) is believed to be involved in a technology demonstration and exhibited curious orbital behavior since it passed very close to the International Space Station within a few weeks of launch in an orbital geometry that would require a number of random factors to align to be just coincidental.

It remains to be seen whether satellite trackers can identify Zuma once it arrives in its Low Earth Orbit and track potential behavior in orbit through visual tracking (also with respect to other spacecraft and/or potential targets on Earth) and/or radio characterization to learn more about its identity.